Bozo Etymology –

That is to Say,

An Etymology of Bozo

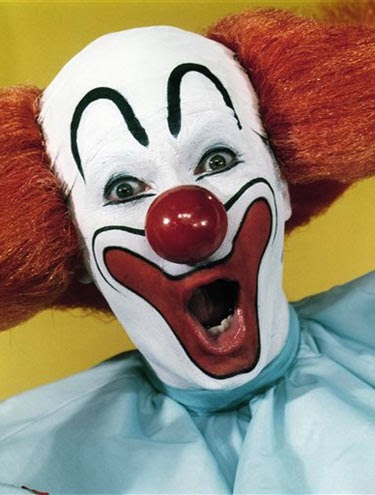

Everyone knows Bozo with his shock of orange hair. Bozo originated as a character on the Capitol

Records’ read-along record, Bozo at the

Circus, issued in 1946. His first

first TV appearances followed in 1949.

In 1956, TV visionary Larry Harmon purchased the rights to Bozo,

developed a children’s show format, and sold Bozo franchises to local stations

across the country. Bozo quickly became

the iconic image we all know and love; his funny name likely playing some role

in his success.

But where did he get his name?

Bozo is a clown, but bozo is also a

pejorative word, meaning

a foolish or incompetentperson.

Since few things are more

foolish than clowns, it would be reasonable to assume that bozo was derived

from Bozo.

As it turns out, however,

bozo pre-dates Bozo the clown by many years.

Merriam-Webster’s (m-w.com) dates the first use of ‘bozo’ to 1916,

origin unknown.

The etymology

dictionary,

Etymonline.com,

dates the first use to1910, derived “perhaps from Spanish bozal, used in the slave trade and also

to mean “one who speaks Spanish poorly.””

The book,

Some Sources of

Southernisms (M. M. Mathews, University of Alabama Press 1948) suggests

that bozo

may have been derived from the

language of slaves, citing

American

Speech (April 1939, p. 97) as saying that bozo “was used among the

Gullahs [(from the Lowcountry

region of South Carolina and Georgia)] as a name signifying great

cheapness.”

These etymological suggestions, however, leave a disconnect

between the meanings of the slave-trade usage and the modern sense of the word

that emerged in the 1910s, and a disconnect between the dates of first use and

purported use among slaves. While a

person who does not speak Spanish well or an extremely cheap person might be

considered foolish or incompetent in certain circumstances, neither poor

language skills nor extreme cheapness are closely associated to the general

idea of being foolish. There is no

apparent explanation for how or why the word emerged when it did. Moreover, by 1910, slavery had been dead for

nearly fifty years and the importation of slaves had ended more than

one-hundred years earlier. If bozo had

been derived from a foreign word or words introduced through the international

slave trade, it seems likely that there would be examples of the word in use

from before 1910.

There is, however, an alternate candidate for the source of

Bozo that has apparently not been considered before.

The new candidate is closer in meaning to the

modern sense of the word than the proposed Spanish or Gullah origins and closer

in time to the reputed dates of first use.

The origin of the word bozo may not even be an earlier word.

The word bozo may derive from the name Bozo,

the name of a comic character from vaudeville and burlesque and the stage name

of one of the actors who portrayed Bozo, Tommy “Bozo” Snyder, a

Ringling-Brothers-trained, circus clown.

That’s right – Bozo the Clown may be derived from bozo which, in turn,

may have been derived (at least in part) from the stage name of a former clown.

[(You can read the history of another, red-headed pop-culture icon here: The Real Alfred E.)]

[See my supplementary Bozo Etymology here: Hobos, Gazabos, Tramps and "The Great Bozo"]

[Listen to Ben Zimmer discuss my research on Bozo, on Slate's Lexicon Valley Podcast at Vocabulary.com]

The History of Bozo

The story of Bozo

begins, curiously enough, with patriotic song-and-dance man, composer

and playwrite, George M. Cohan, who was famously portrayed by James

Cagney in 1942's

Yankee Doodle Dandy. Cohan wrote the sketch comedy,

A Wise Guy, that premiered in 1899. Edmond Hayes played the part of the "wise guy," Spike Hennessey, a working-class piano mover. Other characters in the sketch included a poor actress in search of a rich husband, a bogus English Lord and a

“dangerous horse.”

The actress persuades

Spike Hennessey, “to take the part of [her] father so as to

help her win the hand of a bogus English Lord, who is supposed to have plenty

of money in addition to his title.

The

fun comes from the transformation of an uncouth laborer into a society

gentleman in a dress suit.” Evening Star (Washington DC), January 30,

1900.

Wise Guy also featured, “[n]ew songs, music, dances and

specialties, as well as a bevy of pretty choristers.” Evening Star, January 27,

1900.

Edmond Hayes became famous for his role as "the

original wise guy," Spike Hennessey. He played the role every year for

ten years. In 1909, however, he took a break from the role, starring in the baseball-themed show,

Umpire. In 1910, Hayes returned to the role of Spike Hennessey, but this time in a spin-off entitled,

The Wise Guy in Society, which appears to have been written by Hayes, eager to capitalize on his previous success as Spike Hennessey.

The Wise Guy in Society

featured Spike Hennessey and his sidekick, Bozo, as a team of

working-class piano movers dealing with high-society types in humorous,

culture-clash situations. The brief descriptions of both

A Wise Guy and

A Wise Guy in Society

make it difficult to determine how similar the later show was to the

earlier show, or whether the second show was, perhaps, merely a

repackaged version of the original show. Although the sidekick, Bozo,

is not mentioned in descriptions,

A Wise Guy, at least one report

of the show describes it as featuring more than one piano mover. It is

therefore not clear whether Bozo originated in George M. Cohan's

original sketch in 1899 or with Hayes' spin-off in 1910. In any case,

Bozo originated at least as early as 1910, the same year given as the date of first use of the word 'bozo' by etemonline.com.

The first known reference to Bozo in print is from early 1911:

Lyceum

– “The Wise Guy in Society.”

Gayety,

frivolity, hilarity, and high jingles are promised this week at the Lyceum,

where Edmond Hayes, the original “Wise Guy” will pay a visit.

The

piece is in two parts, the first entitled “McGuire from Slatington,” with John

Daly and Al Canfied as principal comedians, and the second is the “Wise Guy,”

with Edmund Hayes in his familiar role of Spike Hennessy, the piano mover, and Bobby Archer as “Bozo.”

The Washington Times (Washington DC), February 26,

1911. A similar notice appeared in The

Appeal (St. Paul, Minnesota) on April 22, 1911.

In 1912, the Hayes company performed a new show, Piano Movers, again featuring Spike

Hennessey and Bozo in similar comic situations.

A description of the plot discloses that Bozo is both foolish and incompetent

– what we might call a real bozo today:

“Piano

Movers” Move Audience into Hysterics

Edmond

Hayes and Robert Archer, under the employers’ liability act, should be retired

(a long time from now) on a pension.

Edmond Hayes deserves, I can’t think how much, per week, and Robert

Archer merits nearly as much. Hayes has

a “shade on him” because he wrote the sketch (“satire” it is called on the

program) that turned yesterday’s audience at the Orpheum into a shrieking,

hysterical, happy crowd. . . .

What

is “The Piano Movers” about?

About

moving a piano, of course. The

superintendent bosses the job and his crew of workmen is an undersized “gent”

with an expansive grin and a like disposition to wrestle with a can of beer

when he isn’t struggling with an upright.

The piano falls on him finally. I

have never heard that a fallen piano is a conductor of mirth, and a pinioned

mover, squirming beneath it while his superintendent earnestly speculates on

the best way of getting him out, is a spectacle to draw the ultimate shriek of

glee from sane human beings, but I admit that in the case of “The Piano Movers”

both these miracles in mirth were performed.

Enter complaint against yourself if you miss Hayes and Archer when they

move a piano.

The San Francisco Call, September 2, 1912.

In 1914, Hayes was still performing The Piano Movers, but with a new actor in the role of Bozo:

[T]his

week one of the best farces now playing in vaudeville will be presented as the

feature act. It is entitled “The Piano

Movers,” and is presented by Edmond Hayes & Company. Mr. Hayes plays the role of the

superintendent and does all the bossing.

Bozo’s (Thomas Snyder) work is entirely pantomime. Miss Marie Jansen plays the part of a

maid. Hayes is the originator of that

well-remembered and popular character “The Wise Guy.”

The Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), February 8,

1914.

One indication of the success of The Piano Movers, and the

character of Bozo, is that Robert Archer, who had originated the role, featured

that fact prominently in advertisements for his unrelated show, The Janitor, in 1915. The Washington Herald (Washington DC), November 18, 1915.

In 1917, Hayes and Snyder again performed as Spike Hennesey

and Bozo, this time in a new show, Some

Show, that apparently shared a number of plot elements with George M.

Cohan’s original Wise Guy:

Gayety:

“Some Show.”

Burlesque.

Barney

Gerard’s “Some Show” is the current attraction at the Gayety Theater. The company is headed by Edmond Hayes,

creator of “the wise guy” and “the piano mover,” who returns to burlesque after

an absence of six years in vaudeville.

It

is in the latter character that Hayes appears in the present production . . .

. Accompanied by his faithful “Bozo,”

impersonated by Thomas Snyder, he appears in the character of a bogus lord in

order to discourage the ambitions of a title hunter. Many humorous situations come as a result. .

. . The supporting cast includes . . . a

carefully selected beauty chorus of twenty girls.

The Washington Times, March 25, 1917.

Some Show

Some Show

continued into 1918, with Bozo becoming more prominent.

One notice gushes that “Thomas Snyder, who in

his character as “Bozo,” is almost equally famous with Hayes.”

Being equally famous as Hayes was no small

feat; one advertisement from 1918 claimed that Edmond Hayes was the, “Highest

Salary Comedian in Burlesque.” The Washington Time, February 24, 1918.

The same ad, and others from 1918, featured

Bozo more prominently than in earlier years:

Thomas Snyder, the actor who played Bozo, also gained some

personal notoriety and took on the name Bozo.

A newspaper article recounted the story of his life, while noting that

“no one can explain the name”:

Gayety Comedian Started Life in

Quick Lunch Emporium.

Bozo – no one can explain the

name for you’ll have to go to see the “piano mover” in Barney Gerard’s “Some

Show” to understand it all.

But here’s a little history of

the side-splitting comedy side-kicker of Edmund Hayes, who is playing in a

pantomimic role at the Gayety all this week.

But here’s a little history of

the side-splitting comedy side-kicker of Edmund Hayes, who is playing in a

pantomimic role at the Gayety all this week.

Bozo – or Thomas Snyder as he

was then, left home when but a little bit of a shaver an odd dozen years old –

and landed in Chicago dead broke. Work

in a restaurant kept him living, barely living – until Ringling Brothers Circus

came along.

The noisy slapstick artists

attracted young Snyder more than did running orders of “ham-an’” and he joined

the circus as a clown. Traveled with it

six years, too, alternating between the circus ring in summer and the

restaurant in winter.

Then while Snyder was in New

York, pretty much down on his luck, came Edmund Hayes, and asked him if he

could do “Bozo.” Said Snyder: “I can eat

it up.”

A trip to the Colonial Theater

– a tryout of the lines – and Bozo was created.

And since then, thousands of burlesque fans have been delighted and

convulsed by the actions of the “silent man” playing opposite to Edmund Hayes –

Thomas Snyder – alias Bozo.

The Washington

Herald, February 28, 1918. The comment, "no one can describe the name," suggests that the word bozo did not pre-date the character; if the word existed independently from the character, one might explain the name with a cheap pun.

Bozo Snyder was so successful in the role of Bozo that he

would return to Gerard’s Some Show in

1920, but this time as the headliner, without Hayes. Hayes had moved on to a new show, The Night Owls. But even Hayes, the erstwhile “highest salary

comedian in burlesque” would not leave Bozo behind completely. An advertisement for The Night Owls, touted, “Edmond Hayes, And His Own Big Company,

With Mr. and Mrs. BOZO,” with the word Bozo set apart in large font, the same

size font as his own name and the name of the theater. The Evening Public

Ledger (Philadelphia), March 20, 1920.

Curiously, however, Snyder initially tried to abandon the

name Bozo.

One notice for his show lists

him merely as Tommy Snyder (The Washington Herald, Januray 15, 1920) and a

second advertisement lists him as, Tommy “Bevo” Snyder.

The Washington Times, January 15, 1920.

The use of Bevo is explained by a notice in

the trade magazine,

New York Clipper

(an entertainment industry weekly that would later be absorbed into

Variety):

IT’S

“BEVO” SNYDER NOW

“Bevo”

Snyder is the appellation under which Tommy Snyder, hitherto known as “Bozo,”

desires to be known. He is to be the

featured comedian next season with Barney Gerard’s “Some Show” on the American

Wheel. Snyder is under contract to

Gerard for five years and, due to the fact that several other comedians are

known as “Bozo,” it was seen fit to change Snyder’s name.

The New York Clipper, June 18, 1919, page 21. The name Bevo was borrowed from the

Anheuser-Busch company’s prohibition-era non-alcoholic malt beverage. What a bozo – changing his name was probably

one of the most foolish and incompetent decision he could make. He realized his mistake, however. Advertisements for Some Show less than three weeks later list him as “Bozo” Snyder.

The Evening World (New York), February 9, 1920.

Tommy “Bozo” Snyder’s success continued in 1921, when he

performed in Barney Gerard’s Follies of

the Day and signed a contract to make motion pictures:

Burlesque

Comedian Signs Contract Effective at End of Present Season.

Tommy

Snyder, better known as “Bozo” to the followers of burlesque, and who is

featured comedian with the “Follies of the Day” at the Gayety this week, will

soon leave the fields of burlesque for that of comedy pictures.

“Bozo”

has had several offers relative to an appearance in the comedy line of the

cinemas and has each time, refused them.

Through his manager, Barney Gerard, Snyder was enticed to sign a

contract that calls for his appearance on the movie lots immediately after the

close of the current burlesque season.

For

eight years Snyder has delighted burlesque patrons with his comedy and during

the last four years he has worked the comedy part of the show in

pantomime. He is known as the “man who

never speaks.” Aside from that he has a reputation of having the most grotesque

and true-to-life tramp make-up ever used by any comedian using the tramp character.

The Washington Herald, September 29, 1921.

I was unable to find out what happened to Snyder’s movie

career, but the difficulty of finding information suggests that it did not go well.

However, the character of Bozo may have appeared on film in Mary Astor's 1926 movie, The Wise Guy. The plot is not directly related to the plot of Cohan's The Wise Guy or Hayes' A Wise Guy in Society. It does, however, involve a troupe of vaudevillians, one of whom is listed in the cast, as "The Bozo."

Tommy "Bozo" Snyder performed with

Follies of the Day at least into into 1922 and continued performing as Tommy "Bozo" Snyder into the 1950s. He also made the leap from vaudeville and burlesque to Broadway. In 1928, the

New York Times reported that the comedian about whom, "[t]hose who go to the burlesque shows have been screaming this long time about . . . "Bozo"--yes, "Bozo"--Snyder," was "on Broadway at last." December 2, 1928. "Bozo" Snyder later played the "second paperhanger" and the "2nd Rube" in

Michael Todd's Peep Show, a girlie revue that played 278 performances at the Winter Garden Theater from June 1950 through February 1951 (Michael Todd later developed the

Todd AO 70 mm film process).

Bozo, the Ringling-Brothers-trained, silent tramp clown, also performed internationally and may have influenced the more famous "Little Tramp" from silent film, Charlie Chaplin:

WORLD'S FAIR VARIETIES

"TOMMY

"BOZO"

SNYDER,

the principal comedian of the World's Fair Varieties, the latest American

flesh-and-blood revue, which will open at the "Mayfair Theatre on May 12,

is said to have been acclaimed by the king of pantomime, Charlie Chaplin, as

"the best and most original pantomime comedian I have ever seen.''

The Sydney Morning Herald (Australia), May 4, 1939.

TOMMY "BOZO" SNYDER

Acknowledged by Charles Chaplin

to be the pantomimic

comedy genius of the age.

The Sydney Morning Herald, May 6, 1939.

Hayes’ and Snyder’s success and long tenure in

their roles as the hapless piano movers could well have sparked the use of bozo

as a word meaning foolish or incompetent person. The first recorded mention of Bozo in print was in February 1911, mere weeks after the earliest,

purported earliest date of use of 1910 and five years before Merriam Webster’s

earliest date of first of 1916. Bozo seems to have been foolish and/or

incompetent, consistent with the modern sense of the word bozo. Both the timeline and character of Bozo are

in near perfect agreement with the modern sense of bozo and the dates of first use.

The Use of Bozo as a Word

I could not find any uses of bozo, in the sense of a foolish

or incompetent person, prior to 1922.

However, I did find two uses of the word in 1922:

Here

comes a slugger to the bat; wow, Say that bozo murdered that.

The Daily Ardmoreite (Ardmore, Oklahoma), April 11, 1922;

The

second day of the hearing ended in a riot five minutes after court convened,

when the prisoner, Garret Whoozus McKenna, rose in court and presented Judge

Bozo with a nice, red apple.

The

second day of the hearing ended in a riot five minutes after court convened,

when the prisoner, Garret Whoozus McKenna, rose in court and presented Judge

Bozo with a nice, red apple.

The Washington Times, May 21, 1922.

A comic strip from 1922 used the name Bozo in a

bit about trying to choose baby names:

The word was well-established by 1931, when both Laurel and

Hardy and the Marx Brothers used the word bozo in separate films.

In

One Good Turn, near

the end of the film, Laurel yells at Hardy, "Come out of there, you big

bozo!"”

In 1932, Laurel and Hardy

would star in Hal Roach’s Academy Award-winning comedy classic,

The Music Box.

The

Music Box is a story about two tramp-like piano movers, a bossy one and one

who doesn’t talk so much, moving a piano into the home of a high-society couple;

a piano falls on top of one of the movers and the cast includes a dangerous

horse.

While it is impossible to know

how closely Laurel and Hardy’s piano-moving difficulties compare with Spike and Bozo’s

piano-moving problems, the similarity is intriguing.

The Marx Brothers also used the word bozo on film in

1931.

The following exchange takes place

during the film,

Monkey Business:

Alky Briggs: “Say, I can help you bozos!”

Groucho: “That’s Mr. Bozos to you.”

Alky Briggs: “Alright, Mr. Bozo.”

The Marx Brothers had been direct competitors of Bozo Snyder

in burlesque. A 1919 advertisement for

Barney Gerard’s Follies of the Day,

which Bozo Snyder would join in 1920, ran directly beneath an advertisement for the 4 Marx Brothers. Clearly, the Marx Brothers were in a perfect position to have been familiar with Bozo.

Which came first – Bozo or bozo?

The fact that a character and an actor named Bozo both originated at precisely the same time that the word bozo is believed to have taken root is not necessarily proof that Bozo begat bozo. Hayes (or Cohan) might just as easily played off the meaning of the new word in selecting a name for thier foolish or incompetent character.

This begs the question, which came first, Bozo or bozo? As discussed above, it seems that if bozo had been

in use prior to 1910, there would be examples of the word in use. Of course, if Hayes (or Cohan) had chosen the name for specific comic effect when the word was new, it might be difficult to prove otherwise. However, I am inclined to believe that the Character

spawned the word.

The name Bozo is a traditional Serbo-Croatian name from the Balkan region of Europe.

Serbians and Croatians migrated to the United States in large numbers during the great migration from 1880 through 1914. The largest concentration of Serbians and Croations in the United States is in Pennsylvania, concentrated in the mining and steel towns of Western Pennsylvania. Perhaps not so coincidentally, Tommy "Bozo" Snyder, whose real name was Thomas Bleistein, was from Bedford Pennsylvania which is located in southwestern Pennsylvania, about half-way between Harrisburg and Pittsburgh.

The name Bozo was also known, to some degree, throughout the United States in the

early 1900s.

Newspapers from the period

reported, for example, about a young, Dalmatian stoway named Bozo Gacion (The

Manning Times (Manning, South Carolina) July 2, 1902), the naturalization of a

soldier named Bozo Cuckovich (Weekly Journal-Miner (Prescott, Arizona) February

12, 1919), a “Polander” thief named Bozo (The Minneapolis Journal, August 22,

1902), a lawsuit brought by a plaintiff named Bozo Provovich (Bisbee Daily

Review (Arizona), February 8, 1921), and the death of an “Austrian” (the

Austro-Hungarian Empire) named Bozo Obilovich (Amador Ledger (Jackson

California) May 30, 1902.

Even the man

who aspired to the throne of pre-World War I Serbia was named Bozo:

Was

it a whim of fate that the dream of empire for the Serbs, so nearly realized by

Prince Stephen Duchan six centuries ago should be fulfilled by his lineal

descendant Bozo Gupevic of 1845 Sacramento Street, San Francisco, in this year

of our Lord 1909?

San Francisco Call January 19, 1909. Bozo, who had married well (he inherited

$1,000,000 after the death of his first wife) had lived in the United States

from a young age to avoid assassination.

He was not completely safe in the US, however; his brother was poisoned

in an assassination attempt in Colorado.

World War I would break out a few years later when Archduke Ferdinand

was assassinated in Sarajevo, Serbia. It

was a dangerous time to be Serbian royalty.

I do not suggest that the Bozo was named after the heir to

the throne of Serbia, but that Bozo was a known, common (or at least not

completely uncommon) name among an ethnic group from a recent wave of

immigration. A person named Bozo might have

been expected to work as a piano mover under the direction of an Irishman

(Hennessey) from an earlier wave of

immigration. That the name Bozo may have

sounded at least nominally funny to American audiences may have clinched the

choice of the name.

Without more convincing evidence of the use of bozo to mean

foolish or incompetent before 1910, the choice of the name Bozo as a character

name seems more likely to have been based on the name than on the pre-existing

word, bozo. The word bozo and its

meaning would then have been derived from the character Bozo.

Bozo begat bozo begat Bozo

Which is more believable, that a one-hundred year old or

older Gullah or Spanish word for either cheap or a poor Spanish speaker would

emerge in the pop-culture of the 1910s as a word for a foolish or incompetent

person, or that the name of a famously foolish and incompetent character from the

early 1910s (if not earlier) would emerge in the pop-culture of the 1910s as a

word for a foolish or incompetent person?

That was a rhetorical

question. We may never know for sure.

Pinto Colvig, however, the creator of Bozo in 1946 and himself a former vaudevillian, is quoted as having said that he was first told that he looked like a "bozo" when he dressed like a tramp clown to perform at the

Lewis and Clarke Centennial Exposition in 1905. The story is recounted in the

Pinto Colvig biographical sketch on the Internet Movie Database (IMDB.com):

It was the clarinet that got

Pinto into show business when he was 12. . . . Pinto told the man he could play

"squeaky" clarinet and ran back to the hotel to get his instrument.

He was hired on the spot and given some oversized old clothes and a derby and,

for the first time, white makeup and a clown face. The man told Pinto,

"Now you look like a real bozo" ("bozo" was a name given to

hobo or tramp clowns in those days).

The date of the story pre-dates the first recorded report of Bozo in

Wise Guys in Society by five years. However, it is not clear when Pinto Colvig told the story, or whether it actually happened when he says it happened. Perhaps he was called a 'bozo' at some later time, and conflated the two events in retelling the story years later. Perhaps the Bozo character had actually been performed in the earlier productions of

Wise Guy before 1905, although not mentioned in print until 1911. Colvig is said to have performed in vaudeville in the 1910s and joined a circus band in 1916, which places him in vaudeville at the precise time that Bozo was becoming famous in vaudeville. If it were true that 'bozo' had already been an established generic term for tramp clown, one might expect there to be better evidence of use prior to 1910.

One source written late in Bozo Snyder's career, but before the creation of Bozo the Clown, specifically identifies "Bozo" Snyder as the origin of the word "bozo," meaning a tramp clown, which if true would discredit some of the details in Pinto Colvig's story. The writer Dayton Stoddart credited Sime Silverman, the founder of the entertainment industry magazine,

Variety, with popularizing the word Bozo, among other theatrical slang terms that had previously been confined to the limited cirle of show-biz folk; those terms included, for example, upstage (hog a scene), hoofer (dancer), kibitzer (fellow ready with free advice), burn (to be angry) and "Bozo (tramp, from Bozo Snyder)."

Lord Broadway: Variety's Sime, Wilfred Funk (New York) 1941, page 270-271. The book also reflects the use of the word "bozo" as a jocular form of address conversationally among friends ("'lo bozo;" "'owza bozo?;" "watcha mean, bozo?"). Those conversations all appear to have take place after 1918.

All of the evidence seems to support the theory that the widespread fame of the character "Bozo" and Tommy "Bozo" Snyder, who famously played the character, is the source of the word, "bozo," meaning a foolish or incompetent person. The character Bozo dates from 1910, the earliest reputed date of first use for the word "bozo." The character "Bozo" was performed widely every year from 1910 through 1916, Merriam-Webster's date of first use. The originator of Bozo the Clown admitted that he borrowed the name from an old show-business term for tramp clown, and an independent source (written years before Colvig created his Bozo character) credited "Bozo" Snyder as the original source for that show-business term. Given the lack of evidence of other pre-1910 use and no apparent connection between the Spanish "bozal" or the Gullah word "bozo," it seems likely that the name of the character was chosen from the known, Serbian or Croatian name, and not based on earlier words that were not, first-and-foremost, names.

An anecdote told by another early comic actor, however, would push the first use of the word 'bozo' even further back in time. In his memoir, Twinkle Little Star (1939), the comic actor, James T. Powers, who popularized the character on whom

the image of Alfred E. Neuman was based, quotes an American speaking in an exaggerated English accent in the mid-1880s as having said, "Knock his blasted 'ead off! Shoot the bloomin' bozo at daybreak!" If his recollections from fifty years after the fact are accurate, it would set my entire theory on its head. It is easy to imagine, however (as it is with Colvig), that his 1930s recollections of an 1880s incident may have paraphrased the 1880s dialogue using 1930s jargon.

I, for one, am happy to credit Edmond Hayes and Tommy “Bozo”

Snyder with creating the original Bozo character and launching the word 'bozo' in the English language.

The exposition sparked the

imagination of a writer who, within weeks of the exposition, published a

remarkable essay that predicted, with uncanny accuracy, many of the features of

the world we live in today. The article, The Year

of Grace 2081 – a Forecast of How Affairs Will be Conducted Two Hundred Years

Hence, (The London Truth, reprinted in a

number of American newspapers, e.g. Dodge City Times, November 3, 1881; The Pulaski Citizen, December 15, 1881), reflected on the technological changes of the preceding two-hundred years and imagined the changes that might

occur during the following two-hundred years.

The exposition sparked the

imagination of a writer who, within weeks of the exposition, published a

remarkable essay that predicted, with uncanny accuracy, many of the features of

the world we live in today. The article, The Year

of Grace 2081 – a Forecast of How Affairs Will be Conducted Two Hundred Years

Hence, (The London Truth, reprinted in a

number of American newspapers, e.g. Dodge City Times, November 3, 1881; The Pulaski Citizen, December 15, 1881), reflected on the technological changes of the preceding two-hundred years and imagined the changes that might

occur during the following two-hundred years.

Remarkably, nearly every one of his predictions has already come true,

in one form or another. One big

mistake was his prediction that the use of coal would be

abandoned. He predicted that electricity

would be provided by chemical batteries at every home, instead of by centralized

generation and distribution of electricity generated by coal. But he was right in predicting that people would no longer have to store coal at home and that trains and factories would no longer have to burn coal locally.

Remarkably, nearly every one of his predictions has already come true,

in one form or another. One big

mistake was his prediction that the use of coal would be

abandoned. He predicted that electricity

would be provided by chemical batteries at every home, instead of by centralized

generation and distribution of electricity generated by coal. But he was right in predicting that people would no longer have to store coal at home and that trains and factories would no longer have to burn coal locally.

Granted, many of his predictions

are expressed with a Victorian, Steam-Punk aesthetic that does not quite match

our modern world, but considering that he lived in the Victorian age, his

predictive powers were remarkable. The

essay is also notable in that it includes one of the earliest known uses of the

word Martian (as a noun to describe beings from Mars) and the first-knownfictional account of an invasion from Mars (as opposed to all of the true

accounts) pre-dating H. G. Wells’ War of

the Worlds by fifteen years.

Granted, many of his predictions

are expressed with a Victorian, Steam-Punk aesthetic that does not quite match

our modern world, but considering that he lived in the Victorian age, his

predictive powers were remarkable. The

essay is also notable in that it includes one of the earliest known uses of the

word Martian (as a noun to describe beings from Mars) and the first-knownfictional account of an invasion from Mars (as opposed to all of the true

accounts) pre-dating H. G. Wells’ War of

the Worlds by fifteen years.